Happy Latinx History Month: 3 Latinx Artists Students Should Know

It’s Latinx Heritage Month and (some) schools are honoring the contributions that Latinx people have had on our country and beyond. As one of my school’s administrators, I expect all teachers to expose our students to the histories of communities of color throughout the year. In addition, we celebrate the various heritage months, such as Latinx Heritage Month. This year, every class is spending the heritage months honoring the contributions of artists of color.**

Below, I have included three Latinx artists that I recommend teachers to expose their students to. I have not included Frida Kahlo or Diego Rivera, because if I were teaching, my students would already know who these iconic figures are by this time of the year. In addition, it’s important to expand students’ database of famous people of color so that they understand that there are more than 1,2, or 3 famous people of color who have had remarkable accomplishments. The list I have included is simply the beginning…

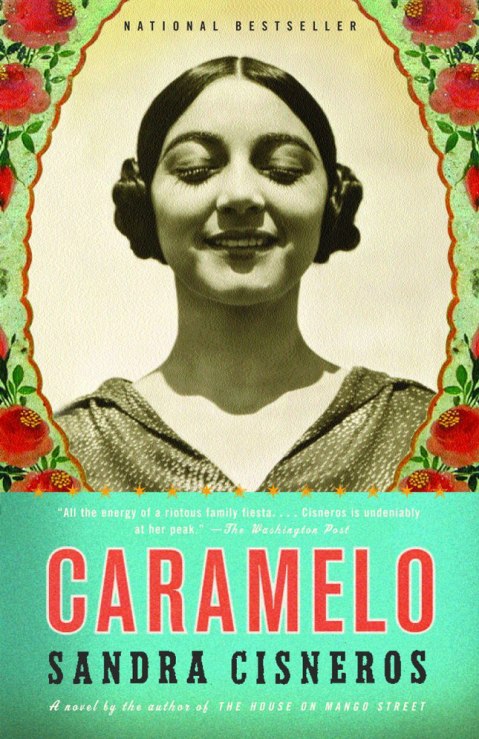

- Rosa Rolanda. Rosa Rolanda was a Mexican-American artist who was born in Azusa, CA. A contemporary of Frida Kahlo, her paintings often feature children, images from folktales, and herself. Rosa was also a subject of many stunning photographs. One of the most recognizable photos, is by Edward Weston. The photograph was featured on an edition of the book Caramelo by Mexican-American writer, Sandra Cisneros.

2.Jean Michel Basquiat. Jean Michel Basquiat was half Puerto Rican and half Haitian and grew up in New York. His art- abstract, sometimes aggressive, and controversial-is attractive to children. The attraction, however, is not necessarily because they think it’s pretty. His art- some featuring dinosaurs, others featuring kings- is familiar to them. When I show his art to elementary children, it often brings up interesting questions around what constitutes art and what doesn’t. What makes art “pretty,” and what is art?

3. Favianna Rodriguez. Born, raised and currently living in Oakland, CA, Favianna Rodriguez is not only a local treasure, but she has made a name for herself as an art/activist. Favianna uses her skills to speak against and for the social issues she believes in. Favianna identifies as an Afro-Peruvian and often uses the features of indigenous and African people in her art. Her work addresses racial justice, sex positivity, and immigration rights. Her Migration Butterflies have become iconic throughout the country and in Mexico, reminding people that migrating from place to place, country to country, is not only natural, but beautiful. Go to her tumblr page to view her art and learn about the work that she does for communities of color: http://favianna.tumblr.com/.